“The Intelligent Investor” by Benjamin Graham is a wonderful book and a profuse source of ideas. Some of them are fairly simple to implement for an individual investor (like the 25-to-75-percent rule). Others are less obvious and can be easily misinterpreted. One good example is a principle of market sentiments:

The market is a pendulum that forever swings between unsustainable optimism (which makes stocks too expensive) and unjustified

pessimism (which makes them too cheap). The intelligent investor

is a realist who sells to optimists and buys from pessimists.

(citation taken from the preface notes by Jason Zweig, but the idea is repeatedly reiterated throughout the book)

While the idea sounds reasonable and intuitive, it’s not clear how to use it in practice. How to understand if investors are too pessimistic? And how much optimism is too much to be sustainable? How to measure the sentiment when half of the internet is screaming about the upcoming collapse of financial systems, and the other part is absolutely sure that line always goes up?

NAAIM Index

I thought that I found all answers when I first heard about US National Association Of Active Investment Managers and their very own NAAIM Exposure Index. What they do is basically gather data on active money managers’ exposure to the equity market. The range of responses is from -200 (leveraged short) to 200 (leveraged long). Then the data is averaged and usually results in a number somewhere between 0 and 150. And it looks like most of the dips correspond to market dips:

(Graphs taken from https://naaim.org/ on March 2nd 2025)

NAAIM vs S&P500

Obviously, I could not resist the urge to try to predict the market using this index. By market, I mean S&P 500, which is not perfect, but a very popular representation of it. The time frame of the research starts in July 2006 and ends in December 2024. And I started with plotting 1-year market deltas versus NAAIM Index values, as the simplest possible measure:

As you can see, there’s almost no correlation visible. The best approximation obtained from linear regression has a pretty low coefficient of determination:

R-squared: 0.004146148498059832

Mean Squared Error: 0.029878859482074673

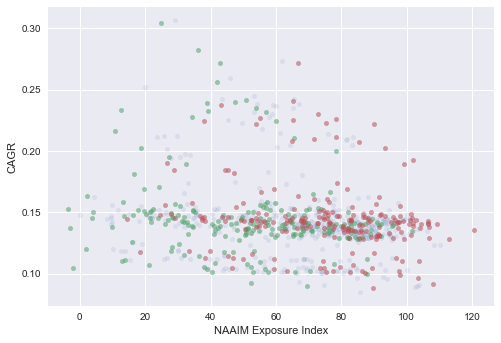

For a good linear correlation, it would be close to 1. In a pursuit of better results, I tried plotting the Compound Annual Growth Rate instead of the 1-year delta:

R-squared: 0.04058949439695614

Mean Squared Error: 0.0008681478096842283

Pearson correlation: -0.2014683458932354

Here correlation is more pronounced. The coefficient of determination is 10 times higher (however, still very far from 1). Pearson’s coefficient of correlation suggests a weak negative relation between the exposure index and future returns over the years.

Picking days

Theory mathematicians love good statistical results, applied mathematicians prefer cash. As some years offer low index values and high resturns, others show overexposure and expensive market. However outliers exists on the graphs, as well as good bying opportunities each and every year. Therefore I tried to identify those.

Relative to the moving average

Hypothesis #1: Low/high values relative to the NAAIM Index moving average offer better/worse results, respectively.

R-squared: 0.0015039742018334579

Mean Squared Error: 0.0008942895444651768

Pearson correlation: -0.03878110624819058

Unfortunately, not.

Local one-side extremums

Hypothesis #2: Values of the index lower than previous X values provide better returns.

Green dots are local minimums in the last 5 values (5 weeks in real time), red dots are local maximums. A difference exists, but can be considered negligible:

Mean (green): 0.1455158309195501

Mean (red): 0.14480137385856384

Conclusions

I spent quite a lot of time thinking about possible applications of this index-market relation, built a few trading strategies, and ran backtesting on them. For now, they all failed. Why? Here’s my thoughts about it:

- Delay: The index is published once per week.

- Exposure could easily change during that time

- The market reflects any publicly available information faster

- Incompleteness: index is gathering information from active managers who decided to disclose it. Massive hedge funds and US congressmen/congresswomen most likely don’t do it

- Accessibility: all public and easily accessible information quickly stops providing any benefits, as other market participants also use it

And returning back to Graham, Zweig, and their advice: I still don’t know how to sell to optimists and buy from pessimists. Unfortunately.